Recently on Netflix, I watched a sad and very disturbing program called The Keepers, "a seven-part docuseries about the unsolved murder of a nun and the horrific secrets and pain that linger nearly five decades after her death", so I am posting here various articles and such that are connected to this crime.

Who Killed Sister Cathy?

45 Years Later, the Search for Answers Goes On.

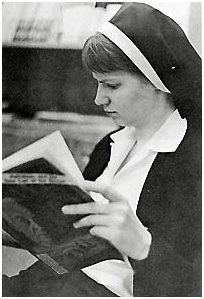

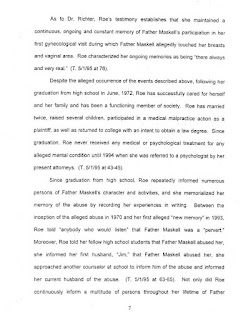

COURTESY THE SETON KEOUGH HIGH SCHOOL

COURTESY THE SETON KEOUGH HIGH SCHOOL

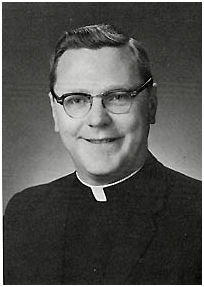

COURTESY DON MALECKI

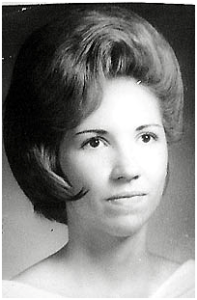

COURTESY JOHN ROEMER

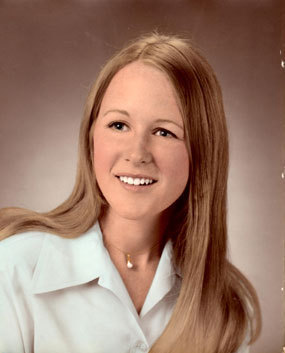

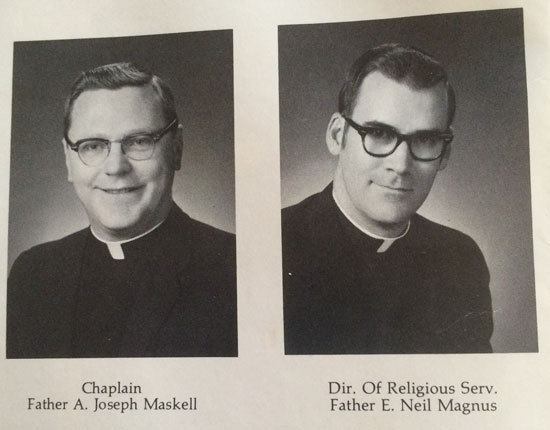

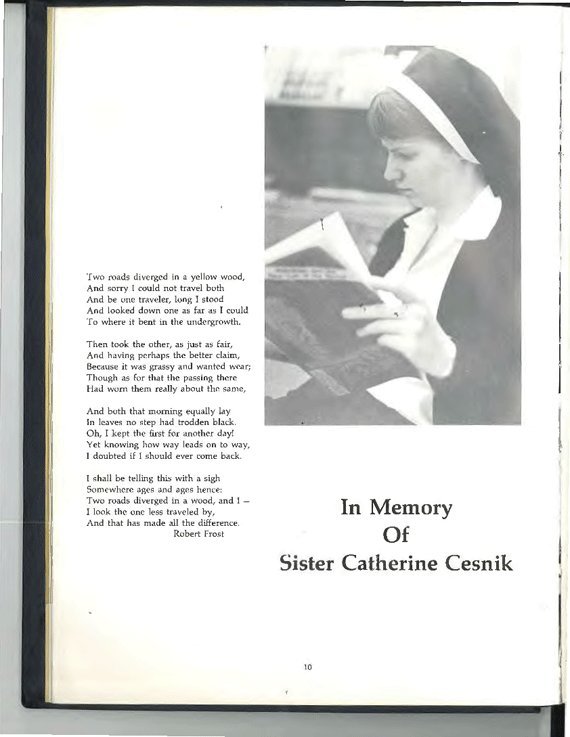

YEARBOOK: (from top) Photographs of Sister Catherine Cesnik, Father A. Joseph Maskell, Joyce Malecki, and Baltimore County Police Capt. Bud Roemer dating from around the time Cesnik and Malecki were murdered

By Tom Nugent

(NOTE: Link to Tom Nugent's blog: https://insidebaltimore.org/)

The old man sat on a metal folding chair in his Essex garage. His big right hand reached out to a wooden table, to a faded police autopsy photo lying there.“Do you see that hole in the back of her skull?” asked Louis George “Bud” Roemer, a retired homicide detective formerly with the Baltimore County Police Department. Wrinkled and white-haired, he pointed to one side of the yellowing photograph he had dug out of a box of files. “That hole is perfectly round, and about the size of a quarter.“I’ve studied that photo over and over again, trying to imagine how she might have died,” he said. “A hole like that—it looks to me like it could’ve been made with a ball-peen hammer.”He paused for a moment, as he recalled the still unsolved murder of Sister Catherine Ann Cesnik, whose body was discovered 35 years ago this month.

“It might have been a hammer,” Roemer continued. “Or maybe a tire iron. Or maybe it was a priest’s ring—one of those heavy gold rings a lot of Catholic priests wear. A priest’s ring would make a hole like that, if he hit her hard enough.”

He fell silent, and leaned back in his chair. He was struggling with diabetes, he said, and talking about the Cesnik case always left him feeling fatigued, and frustrated.

“Every homicide cop has one case that haunts him to the end of his career, and Sister Cathy is mine,” Roemer said. “I sure do wish we could close this one out, before I kick the bucket.”

The body of the 26-year-old nun was found Jan. 3, 1970, in southwest Baltimore County. The circumstances surrounding the case were mysterious and disturbing at the time; in the wake of a City Paper investigation, those circumstances seem even more disturbing now. Years after Cesnik’s murder, a lawsuit documented numerous findings of sexual abuse at the Catholic high school for girls where Cesnik taught shortly before her death. City Paper’s investigation also reveals that a second young murder victim (killed only four days after Cesnik vanished, and only a few miles from where the nun died) attended the same Catholic church where the alleged sex-abuser had been serving as parish priest.

The baffling crimes both remain unsolved to this day. And yet the FBI and Baltimore County Police Department—both of which have recently opened formal reinvestigations into the killings—say they haven’t attempted to make any connection between them.

Roemer helped to solve more than 150 murders during his 23 years as a county cop before retiring as a major in 1975. But he never found the killer of Sister Catherine Ann Cesnik; he died of complications from diabetes on June 10, at age 79. But in interviews conducted before his death, he found these so-far-unexamined connections deeply upsetting. “The more you look at the Cesnik murder case, the more it looks like somebody was trying to cover something up,” he said.

“There was something wrong at the Catholic high school where Sister Cathy taught,” Roemer said while reviewing evidence previously unknown to him. “What you had there was a whole lot of sex going on among priests and students. Can you imagine the scandal, in 1970, if that stuff had ever come out in a trial? Hell, it could have blown the lid right off the Church!

“It doesn’t make any sense to me. Never did. No, there was something going on at that school, and it all came to a head. And when it did, Sister Cathy wound up on the garbage dump with her skull caved in.”

Bud Roemer always drank his coffee black. He was in the middle of his third or fourth cup on the morning of Jan. 3, 1970—a Saturday—when the telephone rang: “Captain Roemer, it’s for you. Halethorpe Precinct.”

Roemer picked up the phone. As the commander of the “M Squad”—the Major Crimes Investigative Unit at Baltimore County Police headquarters in Towson—he was in charge of all criminal investigations involving murder, rape, and armed robbery.

It had been a busy week. Along with their usual caseload of tavern stabbings and liquor store holdups, the dozen officers in the M Squad had been doing their best to help out with a continuing Baltimore City Police investigation into the strange disappearance of youthful teaching nun, Sister Cathy Cesnik, two months before.

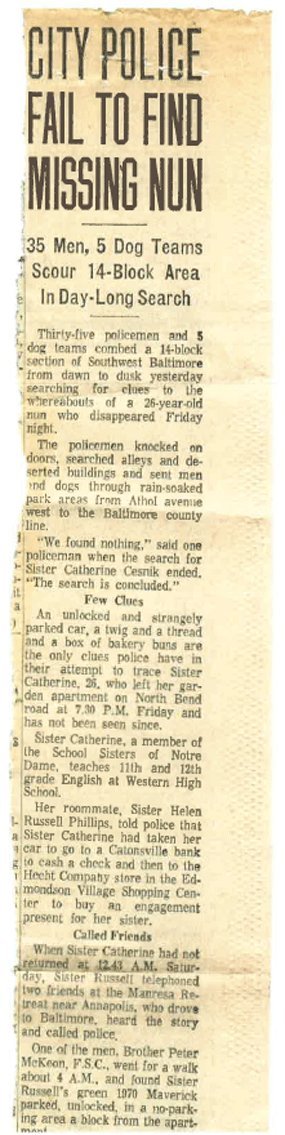

In heavily Catholic Baltimore, the apparent abduction of a well-liked, attractive member of the School Sisters of Notre Dame was big news. Day after day, The Sun and News-American had been giving the story prominent play, while running one dramatic headline after the next: “City Police Search for Missing Nun: 26 Officers Combing Area With K-9 Corps Dogs.”

Described by students and fellow teachers alike as a dedicated, enthusiastic English and drama teacher, Cesnik had vanished on Nov. 7 during a brief, early evening trip to a shopping center about a mile from the Westgate apartment she shared with another Notre Dame nun, Sister Helen Russell Phillips. For almost two months, state and local police investigators had been unable to find a trace of her.

The caller was an excited uniformed police officer in the Halethorpe Precinct of the county police department. Talking fast, the officer told the M Squad captain that two hunters had just called to report what looked like a “woman’s body” lying near a garbage dump off Monumental Avenue, in an isolated, wooded area in the southwest Baltimore County community of Lansdowne.

Moments later, Roemer and several members of the M Squad climbed into one of the department’s unmarked black Plymouths for the 20-mile ride to Lansdowne.

“It was snowing when we got to the dump, and cold as a sonofabitch,” the detective recalled in the spring of 2004. “The body was pretty much covered by snow, but it didn’t take us long to figure out who she was. When I walked up on that dump, I said, ‘Hello, Cathy Cesnik.’

“She was lying on her back, on the slope of a little hill, with her purse and one shoe a few feet away. As soon as we opened the purse, we found a prescription bottle with her name printed on it.

“We worked that crime scene all day long. We called in the medical examiner and we asked for an autopsy right away. We went through our standard procedure, that’s all. I guess we spent four or five hours out there, and it was nearly dark when we finally sent the body off to the morgue.”

Like Roemer, retired Baltimore County Police Capt. James L. Scannell says he has never forgotten finding the nun’s body on the frozen field that day. “I remember her blue coat, and the purse nearby,” says the 74-year-old Scannell, who spent 37 years as a county police officer before retiring in 1992.

“You gotta remember, she’d been laying out on the dump all this time, and the varmints had gotten to her,” Roemer added. “So whether she was raped or sexually molested, I don’t know. And I don’t think anybody ever will know, because the [Baltimore County] medical examiner reported [in his autopsy] that it was impossible to determine if the nun had been sexually assaulted.”

Although the grisly scene would trouble some of the investigators for years, Roemer remained unfazed. “I was used to it by then,” he recalled. “I’d seen a lot of violence during my years as a detective, and after a while you realize it’s just part of the job.

“But I took my job to heart, and I put everything I had into it. When we were working a murder case like the one with Sister Cathy, a 12-hour day was strictly routine.”

The next morning, a Sunday, Capt. Roemer and his M Squad detectives threw themselves into what would become a fruitless five-year quest to identify Sister Cathy Cesnik’s murderer.

They started with the Maryland Medical Examiner’s autopsy report, which stated that the teaching sister from Baltimore’s Archbishop Keough High School for Girls had been beaten to death. The nun had died of blunt-force trauma to one side of her head—along with a blow that had left a round hole in the back of her skull.

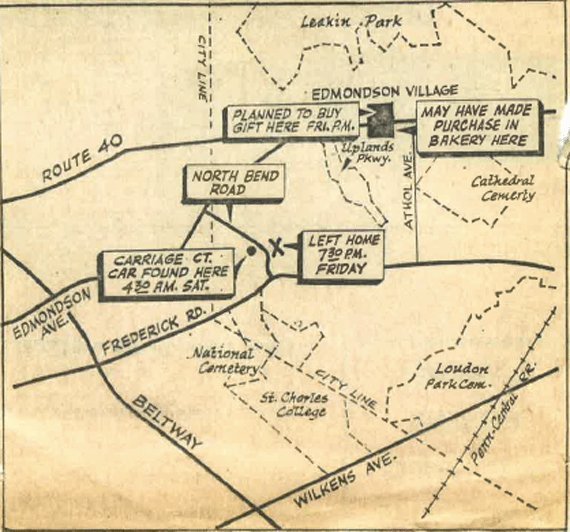

Mulling the autopsy, Roemer soon found himself contemplating a likely scenario: A stranger had probably abducted Cesnik from the Edmondson Village Shopping Center on Edmondson Avenue near her apartment, where she’d gone to cash a check and buy some dinner rolls at about 7 p.m. on the evening of Friday, Nov. 7. In all likelihood, the unknown assailant had then killed the nun and dumped her body about five miles away, in Lansdowne.

But his hypothesis was contradicted by one troubling fact: The nun’s car, a green 1969 Ford Maverick, had been parked near her Carriage House apartment complex only a few hours after she drove off to the shopping center.

“I’d been working homicide for about 10 years when Sister Cathy was killed,” Roemer said, “and I’d never heard of a ‘random killing’ where the stranger who kills you carefully returns your car to your apartment house. In that situation, the killer usually wants to get the hell away from there. The last thing he wants is to return to the area, where he might be spotted driving the victim’s car.”

How had the dead woman’s Ford gotten back to her apartment complex? In an effort to solve the puzzle, Roemer sat down with two Baltimore City detectives—Harry Bannon and Tony Glover, now both retired—who had directed the search for the missing nun during the previous two months. What Roemer learned from the city detectives was also deeply troubling.

For starters, Roemer was surprised to discover that the nun’s roommate—Sister Helen Russell Phillips—had not called the police after becoming alarmed when Cesnik failed to return from the brief shopping trip by 11 p.m. Instead, Phillips had phoned a Catholic priest living in a Jesuit community known as Manresa, located near Annapolis. Within a few minutes, Jesuit Father Gerard J. (“Gerry”) Koob—accompanied by a second Catholic brother, Peter McKeon—climbed into his car and drove to the Carriage House Apartments.

Koob and McKeon questioned Phillips about Cesnik’s shopping trip, and somewhere between midnight and 1 a.m. the three of them called the police and gave them a telephone report describing the nun’s disappearance. After several more hours of conversation, they later told detectives, they decided to take a walk around the neighborhood in order to calm their nerves. Around 4 a.m., while walking, they spotted Cesnik’s green Ford Maverick, parked at an odd angle, directly adjacent to the Carriage House parking lot.

Roemer listened carefully to all of this and quickly decided that he didn’t like it. “We made the decision that it was time to ‘put the heat on Koob,’” he said in the spring of 2004. During the many hours of interrogation that followed, Roemer asked the Jesuit priest again and again: “What, exactly, was the nature of your relationship with Sister Cathy Cesnik?”

At first, Roemer recalled, Father Koob insisted that the two were simply good friends who enjoyed a great deal of purely “platonic affection” for each other. “That’s fine,” he told the priest. “But why would Sister Russell have called you instead of the police after Cathy disappeared that night?”

Roemer understood the reason better a few days later, after visiting Father Koob’s residence at the Manresa Jesuit community. There, he said, he came across a letter Cesnik had written to the priest on Nov. 3, only a few days before she disappeared. (In an interview, Koob told City Paper he willingly gave the letter to the detective, in order to help the police with their investigation.)

Roemer read the letter, which did not reach Koob until after the nun’s murder, and concluded that the actual relationship between nun and priest had been far from platonic.

Interestingly enough, the letter begins with a reference to a song about what might happen if the nun suddenly vanished:

My very dearest Gerry,

“If Ever I Should Leave You’ is playing on the radio. I’m all curled up in bed. My ‘period’ has finally arrived, ten days late. . . . So you might say I’m moody. . . . My heart aches so for you.

The letter goes on to outline Cesnik’s struggle with her relationship with Koob:

I must wait on you—your time and your need—even more than I had before. . . . I think I can begin to live with that more easily now than I did two months ago, just loving you . . . within myself. . . .

Regardless, Cesnik had a future outside the church with the priest firmly in mind: “I must tell you, I want you within me. I want to have your children. . . .”

When Roemer showed the priest the letter, the detective later recalled, Koob “quickly broke down and admitted he was having sex with the nun. That didn’t make any difference to me, of course—that was their business. But it did put me on guard, because it told me that the Catholic Church would have a whole lot to lose, if that letter should ever get out.”

But Koob, today a 63-year-old married Methodist minister living in another state, has insists that he never had a physical relationship of any kind with Sister Cathy Cesnik.

She lies buried on the side of a steep hill in Sharpsburg, Pa., a threadbare suburban town directly across the Allegheny River from Pittsburgh. Her granite headstone offers the eye only four stone-carved words: sister catherine cesnik ssnd 1942-1969.

Her father, Joseph Cesnik, a former Pittsburgh postal worker, rests a few feet higher up the slope, along with several of his Slovenian-American ancestors.

Cathy Cesnik’s cousin Gregory Cesnik, now 46, attended his aunt’s burial service in January 1970. “I was only 12 years old at the time,” recalls Gregory Cesnik, today a certified public accountant. “But I’ve never forgotten the sorrow everybody felt or the look of anguish on her father’s face.”

Shrouded in snow on a recent winter morning, St. Mary’s Cemetery could be seen only dimly from the Lawrenceville section of Pittsburgh, on the other side of the slate-gray river. It was here, in a crowded neighborhood punctuated by half a dozen clattering steel mills, that Catherine Ann Cesnik lived out her 1950s childhood.

Early each morning during the school year, Cathy and her sisters left their family’s modest bungalow at 1023 Downlook St. and walked half a mile to the tiny parochial school that adjoined St. Mary’s Assumption on 57th Street. There she absorbed a thoroughly typical 1950s Catholic grade-school education—the kind of prayer-laced, deeply reverent tutelage provided in that era by the School Sisters of Notre Dame teaching order of nuns, who operated the school during Cathy’s childhood.

Intensely religious, Cathy was deeply impressed by some of her dedicated Notre Dame teachers—so impressed that by the time she moved on to St. Augustine Catholic High School in 1956 she was already thinking about entering the Notre Dame convent and becoming a School Sister herself. After graduating, Cathy entered the Baltimore Province convent of the School Sisters of Notre Dame on Sept. 29, 1960, as a “postulant,” or candidate for the sisterhood. After seven years of study, she professed her “final vows” on July 21, 1967.

The youthful nun had already begun her teaching career in 1965 at the newly opened Archbishop Keough High School on Caton Avenue in Southwest Baltimore. During the next four years, she would teach English and drama to several hundred students from the mostly working- class, Irish-American community nearby.

Gemma Hoskins, who would later enjoy a 30-year career as a public-school teacher—she was “Maryland Teacher of the Year” in 1992—remembers Cesnik as a deeply inspirational figure and a “terrific” teacher. “Catherine Cesnik is the reason I became a teacher,” says Hoskins, 52, today. “I still regard her as the finest teacher I ever had.”

More than a dozen other former Keough students described Cesnik as an outstanding teacher. “She was our ‘Pied Piper,’” said one, “the kind of teacher you never forget.”

Although Cesnik loved teaching, she appeared to be struggling with some inner turmoil during the spring of 1969. “To me, she seemed stressed out, perhaps even on the edge of a nervous breakdown,” one former student who asked not to be identified says. “She was exhausted and extremely nervous, and she missed a lot of school during the spring months.”

One of the possible reasons behind Cesnik’s apparent stress became clearer in June of that year, when she asked permission from her Notre Dame superiors to enter a period of “exclaustration,” an experiment in which she would live outside the convent, while also substituting civilian dress—skirts, blouses, dresses—for the traditional nun’s habit.

Permission was granted and Cesnik moved into a two-bedroom apartment at the Carriage House on North Bend Road. At the same time, the nun decided on a second experiment: Instead of teaching at Keough during the 1969-’70 school year, she would serve as a “missionary” teacher at a public school, Western High.

During the first few months of that school year, Cesnik shared her Carriage House apartment with a friend and fellow nun, Sister Helen Russell Phillips, who had also stopped wearing the habit and was also teaching at Western.

In interviews with City Paper, two former Keough students remembered their frequent visits to Cesnik at her Carriage House apartment, only a few months before she died. “I was also friends with Sister Russell, her friend and roommate, when they moved to the apartment on North Bend Road,” Kathey Payne of Ellicott City recalls. “I visited them there during that summer and I did some sewing for Sister Russell.”

Did one or more of the students who were visiting Cesnik’s apartment in the summer and fall of 1969 tell her about the sexual abuse that was taking place at the school? One former student later recounted in a City Paperinterview how she had gone to Cesnik for help after being abused by a priest at Keough, but the most startling evidence comes from now-retired Sister Mary Florita, a former School Sisters of Notre Dame teaching nun.

“I knew several of the kids at Keough,” says Marian Weller of Harrisburg, Pa., the former Sister Mary Florita. “And one of them described to me how three or four girls who were being abused by this priest had gone to Sister Cathy for help. There’s no question but that she knew about the abuse that was taking place during the months leading up to her death.”

Interviewed at length by City Paper, Koob essentially repeated what he’d told Roemer 35 years ago. He says he and Brother Peter McKeon immediately drove to the Carriage House. He says they talked with Sister Helen and then phoned the police to report Cesnik as a “missing person” somewhere between midnight and 1 a.m. A few hours later, around 4 a.m., Father Koob took a walk with the other priest and blundered into Cesnik’s car near the Carriage House.

Koob says that there were no indications that a struggle had taken place in the Ford.

“When we discovered the car, I was careful and I told [McKeon] to be careful,” Koob tells City Paper. “I think we both saw a little wastebasket spilled over—but that did not suggest a struggle to me. I believe Cathy would have frozen up and not struggled.”

For his part, Roemer was convinced that the absence of signs of struggle in the car clearly suggested that “whoever killed Sister Cathy had to be someone who knew her. That’s the only thing that makes sense, once you remember that her car was returned to her apartment complex after she was killed.”

Koob passed two separate lie-detector tests soon after the murder. His alibi—he had eaten dinner and taken in the movie Easy Rider with his priest friend in Annapolis before the call from Sister Helen—proved airtight. According to Baltimore County Police investigators then and now, Koob has never been a suspect in the murder. But some former police detectives continue to believe Koob knows more about what happened that night than he has told investigators.

Even more troubling, two retired investigators tell City Paper that while they were “putting the heat” on Koob, Catholic Church officials conferred with high-ranking police officials about the case. “We thought Koob was about to break,” retired Baltimore City homicide investigator Harry Bannon says. “And then the church lawyers stepped in and they talked to the higher-ups at the police department. And we were told, ‘Either charge Koob with a crime or let him go. Stop harassing him.’

“After that, we had to break away from him,” Bannon continues. “And that was a shame, because I’m sure Koob knew more than he was telling. We never did solve the case, and I think part of the reason was that we had to back away from Koob.”

Roemer agreed that his murder investigation “seemed to dry up” after Koob was allowed to walk away from the case. “Nobody ever told me to back off the investigation in order to protect the Catholic Church,” Roemer said. “And if they had, I wouldn’t have done it. But the word did come down from higher levels of the police department that we had to lay off Koob. And I couldn’t help wondering if maybe one of the Catholic officials had gotten to somebody high up in the police.”

For his part, Koob continues to insist that he gave the police everything he knew about Cesnik. He also says she never told him about sexual abuse at Keough, or about any alleged threats against students or teachers who spoke out publicly against the abuse.

In 1994, former Archdiocese of Baltimore spokesman William Blaul told reporters from The Sun that the church didn’t send lawyers to the Baltimore County Police Department to demand Koob be left alone. Current Archdiocese spokesman Sean Caine confirms that the Archdiocese did not interfere in the investigation.

By the time Bud Roemer retired from the Baltimore County Police Department in 1975, the Cesnik murder case had gone completely cold. For the next 20 years, the files and the evidence in the sensational killing would gather dust in a back room at police headquarters in Towson.

And then the case suddenly flared up again in 1994 after more than 30 men and women with firsthand knowledge of alleged abuse came forward to offer testimony in a shocking $40 million lawsuit. The suit sought damages for two former Keough students who claimed to have been injured by rampant sexual abuse at the school. According to the lawsuit, the abuser had been the school chaplain, a Diocesan priest named A. (Anthony) Joseph Maskell.

As listed in the plaintiffs’ formal complaint, the abuse included “vaginal intercourse, anal intercourse, cunnilingus, fellatio, vaginal penetration with a vibrator, administration of enemas, . . . hypnosis, threats of physical violence, coerced prostitution and other lewd acts, physically striking Plaintiff, and forcing Plaintiff to perform sexual acts with a police officer.”

The list of charges troubled many Catholics in Baltimore. But those dramatic charges were soon eclipsed by testimony from one of the plaintiffs, identified only as “Jane Doe” for her protection, in which she claimed to have been taken to the Lansdowne garbage dump by Father Maskell in late November 1969 and shown the body of a dead nun, as a warning that she should say nothing public about the sexual abuse.

The sensational allegations of “Jane Doe” stunned Baltimore, and no one was more shocked than Roemer, who years later still reacted with amazement: “When I heard about the woman who was supposed to have been shown the nun’s body by Maskell, I could hardly believe my ears. If that was true, it meant the priest would have been involved in this thing up to his eyeballs!”

Until the lawsuit in 1994, Roemer said, he had never heard of Father Joseph Maskell or of the alleged abuse at Keough. His team of sleuths had completely missed this aspect of the investigation.

Although the abuse lawsuit brought in Baltimore County Circuit Court by the two former Keough students (“Jane Doe” and “Jane Roe”) was eventually dismissed on a technicality involving the courtroom admissibility of “recovered memory” evidence in Maryland, the testimony and depositions were so compelling that the Archdiocese conducted its own investigation of Maskell. After reviewing the evidence, church officials formally “revoked the faculties” of the priest and relieved him of his administrative duties as the pastor of St. Augustine’s parish in Elkridge.

Maskell, meanwhile, insisted he was completely innocent of all charges, then died at age 62 from the effects of a major stroke on May 7, 2001. The Archdiocese of Baltimore never reinstated him, after finding the evidence against him to be “credible,” according to archdiocesan spokesman Caine. The Archdiocese also confirmed for City Paper longstanding reports that Father Maskell had kept handguns at the parish rectory where he lived: “After his departure from St. Augustine’s in 1994, guns were found in the residence.”

Shortly before the lawsuit (Jane Doe et al. v. A. Joseph Maskell, et al.) was filed in 1994, “Doe” began telling police and newspaper reporters alike about her alleged trip with Father Maskell to the garbage dump to view the body of the dead nun. As The Sun reported on June 19, 1994, “in interviews with the police and Sun, [Jane Doe] provided details about the body that were known only to investigators at the time, and detectives have not dismissed her claims.”

Former priest Gerry Koob also recalls that investigators of Father Maskell in the mid-1990s told him that Doe had remembered the garbage dump accurately. “I heard nothing about this [the alleged abuse by Maskell and Doe’s trip to the dump] until the mid-1990s,” he says. “It seemed credible when I heard it, because the [police investigator] who told me about it said that the woman who was reporting the sexual abuse said that her abusers had taken her to see Cathy’s body, and that she knew details that had never been publicized.”

Although the preponderance of evidence suggests that Father Maskell committed acts of sexual abuse at Keough, many of his former parishioners, family members, and friends continue to defend him—including former police officers.

“I knew him for many years, and for about 10 of them he was the Baltimore County Police Department chaplain,” says former Baltimore County Police Capt. James B. Scannell, now 73 and retired. “Father Maskell loved to ride around in our police cars, and more than once he rode with me. He was a wonderful priest and a loyal friend.”

Retired Maryland State Police Lt. Col. Jim Jones, former director of personnel, says that Maskell had “done a terrific job” as the chaplain for the State Police for more than decade: “He was a wonderful priest, and he counseled many of our troopers and helped them a great deal.”

Other friends and family members point to the fact that Father Maskell’s brother, Lt. Tommy Maskell, had served with distinction as a member of the Baltimore City Police from 1946 to ’66.

But that same information—that Father Maskell maintained close connections with high-ranking state, county, and city police officials throughout his career as a Catholic priest—troubles several former students at Keough.

“He used to ride around at night in an unmarked patrol car with a cop,” says one woman who told City Papershe’d been abused. “They had a portable flasher they could stick on top of the car, and they would sneak up on kids who were making out and harass them. I remember feeling very frightened and very angry when I saw how Father Maskell and the police were getting away with that.”

On Nov. 13, 1969, six days after Sister Cathy Cesnik vanished, not to be found murdered for two long months, a second young woman—20-year-old Joyce Malecki—was found strangled and stabbed to death in a small creek located on the U.S. Army’s Fort Meade military base in Anne Arundel County, only a few miles from where Cesnik’s body would later turn up. That crime also has never been solved.

Malecki, a secretary for a liquor distributor in the Baltimore area, had been abducted from the parking lot of an E.J. Korvette’s department store in Glen Burnie. After disappearing around 7 p.m. on Tuesday, Nov. 11, Malecki resurfaced the following morning with her hands tied behind her back, lying face down in the Little Patuxent River at the military base. According to the autopsy, she had been strangled and stabbed several times in the throat; cause of death was strangulation.

Understandably, police investigators and newspaper reporters were intensely interested in the possibility that there might be some connection between the two killings, and their speculations were often reported on the front page in Baltimore. But no such link between the murders has ever been established, according to FBI and Baltimore police officials today. (The FBI held the original jurisdiction on the Malecki case because the body was found on a “government reservation.”)

A four-month investigation by City Paper did find some disturbing links between the two crimes:

- An examination of the 1968-’69 Keough yearbook, The Aurora, shows that a gift was made to the school during that year by “The Malecki Family,” the name of which appears on the “Patrons” page.

- Interviews with remaining family members reveal that the Malecki family, which lived in Lansdowne (less than a mile from where Cesnik’s body was found), attended the nearby St. Clement Church. The Malecki siblings, including Joyce, also attended week-long “retreats” as high school students—during which they spent entire days engaged in religious instruction with priests.

- Baltimore Archdiocesan records confirm that alleged abuser-priest A. Joseph Maskell served “at St. Clement (Lansdowne) from 1966 to 1968 and at Our Lady of Victory [located on nearby Wilkens Avenue, about three miles distant] from 1968 to 1970.” The official Archdiocesan record continues: “[Father Maskell] lived and assisted at St. Clement (Lansdowne) while serving at Archbishop Keough High School from 1970 to 1975.”

- Clement Church is located less than a mile from where Cesnik’s body was found, in a very remote area. Says one former high-ranking Baltimore County Police investigator who preferred not to be identified: “Whoever dumped the nun’s body there had to know the area well. That dump was difficult to get to, if you didn’t know your way around, and the nun did not vanish until after dark.”

Says Joyce Malecki’s older brother Donald Malecki today: “One thing I can’t understand is why no law-enforcement officials have ever made this connection or asked us about it.”

When asked about the possible connection between the killings, Baltimore-based FBI Special Agent Barry Maddox tells City Paper that the Bureau “didn’t actually do the investigation” into Joyce Malecki’s death, but turned all of its information over to the nearby Anne Arundel County Police Department. But a spokesman for the Anne Arundel County Police insists that no investigation of any kind had ever been conducted by his police department and referred the inquiry back to the FBI.

For his part, a totally mystified Bud Roemer said he couldn’t understand why “they haven’t all gotten together and run down these leads. If it was me, I’d sure as hell want to check everything out!”

Donald Malecki says he visited the FBI’s Baltimore office three years ago and was told only that “‘we conduct a periodic review of the case, we we’ll contact you if we find anything new.’” He added: “They kept me in the lobby and sent down two 25-year-old kids who tried to reassure me, but they wouldn’t show me the files or talk to me about the case. Instead, they told me that my best chance of finding the killer was to talk to the producers of Unsolved Mysteries on television and try to get them interested in the case.”

After reviewing the new information uncovered by City Paper, FBI spokesman Maddox concluded : “All of these coincidences certainly rise to the level of possible significance for solving both killings. We haven’t ruled anything out, including Father Maskell, and we have gone back to reinvestigate the Malecki killing and possible links to the Cesnik case.”

And 35 years after Sister Cathy Cesnik’s body was found on the garbage dump at Lansdowne, the Baltimore County Police Department’s Cold Case Squad is once again investigating her murder. During a December 2003 interview with City Paper, two detectives on the squad provided a sketchy account of their latest findings.

The two detectives, who preferred not to be identified, acknowledged, “We don’t know what happened to Sister Cathy.” But they go on to say that, having initially reopened the case as part of a periodic review, they don’t consider Father Maskell to be a suspect, based on “early interviews with witnesses” and “signs of struggle” in her car. They said they were operating on a theory that Cesnik was abducted by “a stranger or maybe by someone who knew her” on the night she disappeared. They said they were exploring a theory that an intruder forced his way into her car, drove her to the dump and killed her, then simply returned the car to her apartment complex because he needed transportation in order to get back home.

They said they didn’t believe Father Maskell was involved because of earlier interviews by other investigators with him in 1994 (after “Jane Doe” came forward), although they gave no specifics about those interviews, and because “Jane Doe got some of the details wrong” when she described her alleged visit to Cesnik’s body at the dump. But they cannot account for the fact that Baltimore County Police officials in 1994 were quoted as saying that “Doe” had described details about the dump that had never been made public before.

They also confirmed that they had called Bud Roemer in October 2003 and discussed the case with him. They describe Roemer as a “fine detective, reliable and trustworthy”: “We’re sure that whatever he told you is straight, to the best of his memory.”

Only a few weeks before his death last June, Roemer said that he still hoped the murder of Sister Cathy would be solved some day.

“If all of these new findings are accurate, it looks to me like we’ve got two murders, four days and a few miles apart. And both of the victims seem to be tied directly to the school and the church,” he said. “I just hope they’ll figure it out. I hope we can get closure on Sister Cathy, before I go to meet my maker.”

Story courtesy of BALTIMORE SUN/City Paper

With Netflix's "The Keepers" documentary series on the unsolved killing of Baltimore nun Sister Catherine Cesnik debuting Friday, we chronicle developments in the case, from her disappearance in November 1969 to the present. This timeline will be updated with more archived material in the coming days.

1942 - Sister Cesnik was born in the Lawrenceville neighborhood of Pittsburgh, Pa.

Friday, Nov. 7, 1969 - Sister Cesnik, 26, left her Baltimore apartment for Edmondson Village Shopping Center in the early evening, according to her roommate, Sister Helen Russell Phillips. It was around 7:30 p.m. She lived in the Carriage House apartments in the 100 block of North Bend Road. Sister Cesnik cashed a paycheck for $255 at the First National Bank at 705 Frederick Road in Catonsville. She may have made a purchase at a bakery in Edmondson Village. She was also planning to go to Hecht’s to buy an engagement gift, according to Sister Russell.

Sister Cesnik, an 11th and 12th grade English teacher at Western High School, belonged to the School Sisters of Notre Dame, an order devoted to education. She had previously taught English and coached the drama club at Archbishop Keough High School.

Saturday, Nov. 8, 1969 - Concerned about Sister Cesnik, early in the morning Sister Russell called two friends, Rev. Peter McKeow and Rev. Gerard J. Koob, who drove to Baltimore from Beltsville to comfort her. After hearing Sister Russell’s story, the three called city police to report Sister Cesnik missing. At 4:40 a.m., Rev. McKeow found Sister Cesnik’s unlocked car, a green 1970 Maverick, in the 4500 block of Carriage Court. (other reports have Sister Russell and Rev. Koob also finding the car with Rev. McKeow). The vehicle was towed to the city’s Southwestern District station. Police had received several calls about the “oddly parked vehicle.”

Police, aided by six K-9 Corps dogs, searched until dark yesterday for a 26-year-old Catholic nun, missing from her home since Friday night.

Sister Cesnik, an 11th and 12th grade English teacher at Western High School, belonged to the School Sisters of Notre Dame, an order devoted to education. She had previously taught English and coached the drama club at Archbishop Keough High School.

Saturday, Nov. 8, 1969 - Concerned about Sister Cesnik, early in the morning Sister Russell called two friends, Rev. Peter McKeow and Rev. Gerard J. Koob, who drove to Baltimore from Beltsville to comfort her. After hearing Sister Russell’s story, the three called city police to report Sister Cesnik missing. At 4:40 a.m., Rev. McKeow found Sister Cesnik’s unlocked car, a green 1970 Maverick, in the 4500 block of Carriage Court. (other reports have Sister Russell and Rev. Koob also finding the car with Rev. McKeow). The vehicle was towed to the city’s Southwestern District station. Police had received several calls about the “oddly parked vehicle.”

Police, aided by six K-9 Corps dogs, searched until dark yesterday for a 26-year-old Catholic nun, missing from her home since Friday night.

Monday, Nov. 10, 1969 - Police continued to check tips and leads but don’t resume large-scale searches. Captain John C. Barnhold Jr., head of the city’s homicide squad, said there was “no evidence of foul play” in Sister Cesnik’s disappearance. “We could find no evidence of violence of any kind,” Barnhold said.

Tuesday, Nov. 11 , 1969 - City homicide detectives said they had no reason to believe that the young teaching nun -- who had disappeared four days earlier -- was kidnapped. Police said they were trying to piece together what happened during a two-hour period on Nov. 7, when Sister Cesnik went missing -- at 8:30 p.m., residents saw Sister Cesnik’s car drive into her reserved parking spot; the car was later spotted illegally parked about a block away at about 10:30 p.m.Joyce Helen Malecki, 20, went missing the evening of Nov. 11. She had left her home in Baltimore to go shopping in Glen Burnie and for a date with a friend stationed at Fort Meade Army base. Police begin searching for Malecki.

Wednesday, Nov. 12, 1969 – Malecki’s abandoned, unlocked car was found parked in a lot of a vacant gas station in an area of Odenton called Boom Town. Her car, with the keys still in the ignition, was found by her brother. Her glasses and groceries she had purchased in Glen Burnie were found in the car.

Thursday, Nov. 13, 1969 - Malecki’s body was found floating in the Little Patuxent River by two deer hunters on the western edge of Soldiers Park, a Fort Meade training area. The FBI and military police immediately closed the site. City police continued to check leads in the disappearance of Sister Cesnik.

Friday, Nov. 14, 1969 - An autopsy of Malecki’s body revealed that the victim was stabbed and choked and her hands were bound behind her with a cord. She had a number of scratches and bruises indicating a struggle. The cause of her death was either choking or drowning -- further test were needed to determine the cause. Malecki was described as 5 feet, 7 inches tall and 112 pounds. She had brown hair and brown eyes. Baltimore homicide detectives reported that Sister Cesnik was still considered a missing person with no new leads.

Saturday, Nov. 16, 1969 - Police investigated whether a pair of black high-heeled shoes found near Malecki’s watery grave belonged to Sister Cesnik, who was said to be wearing black shoes at time of her disappearance. “We have no indication that they are Sister Cesnik’s shoes, but we will check it out,” Capt. Barnold said at the time.

Jan. 2, 1970 – Baltimore’s major newspapers, The Baltimore News American, Baltimore Sun and Evening Sun, are shut down by a strike that would last 74 days. Sister Cesnik's body would be found the next day.

Jan. 3, 1970 – Sister Cesnik’s partly clad body was found by two hunters, a father and son, in a remote area in Lansdowne in Baltimore County. The body, partially hidden by an embankment and snow covered, was discovered about 100 yards from the 2100 block of Monumental Avenue. Police said it was probable that Sister Cesnik had been carried to the area or forced to walk there. (A car could not have been driven from Monumental Avenue to where the body was found.). An autopsy revealed a skull fracture caused by a blow to Sister Cesnik’s left temple by a blunt instrument. Baltimore County Police take over the homicide investigation, which remains open to this day.

1992 - The first allegations of sexual abuse are made against Rev. A. Joseph Maskell, a Catholic priest, by two former female students of Baltimore’s Archbishop Keough High School. Maskell denies the allegations, which are investigated by city police.

Maskell grew up in northeast Baltimore and graduated from Calvert Hall College. He trained for the priesthood at St. Mary’s Seminary in Roland Park. He was ordained in 1965. He was a school chaplain and counselor at Archbishop Keough from 1967 to 1975. He served at several local parishes: Sacred Heart of Mary from 1965 to 1966; St. Clement (Lansdowne) from 1966 to 1968 and from 1970 to 1975; Our Lady of Victory from 1968 to 1970; Annunciation from 1980 to 1982; Holy Cross from 1982 to 1992; and St. Augustine’s (Elkridge) from 1993 to 1994. He earned a master’s degree in school psychology from Towson State in 1972. He also earned a certificate of advanced study in counseling from Johns Hopkins University. He served as a chaplain for the Maryland State Police and Baltimore County Police and Maryland National Guard and later the Air National Guard as a Lieutenant colonel.

1992 - Maskell, pastor of Holy Cross Church in South Baltimore, was removed from his position by the Archdiocese of Baltimore following accusations of sexual misconduct.

October 1992 – April 1993 Maskell stayed at the psychiatric hospital, “Institute of Living,” located in Hartford, Conn. He “returned to Baltimore after an evaluation found no psychological or sexual abnormalities,” according to a 1994 Sun article.

August 1993 - Maskell was named pastor of St. Augustine’s in Elkridge after an investigation by the archdiocese did not corroborate sexual abuse allegations, according to the church.

Spring 1994 - A former Archbishop Keough student tells Baltimore County police that Maskell sexually abused her and took her to see Sister Cesnik’s body weeks before it was discovered on Jan. 3, 1970. The student also told police that another man she met in the priest’s office told her he had beaten Sister Cesnik to death because the nun knew of the alleged sexual molestation. Police note inconsistencies in the student’s account.

The student said the priest and the other man – whom she did not identify – warned her that she would suffer the same fate if she told her story to anyone else. Police were unable to verify or disprove the woman’s allegations. But in interviews with police and The Sun, she provided details about the body that were known only to investigators at the time.

July 31, 1994 - Maskell left his parish at St. Augistine’s in Howard County to seek therapy in the face of mounting allegations of sexual abuse. A least a dozen women alleged that Maskell abused them while they were students and he was a counselor at Archbishop Keough during the late 1960s and 1970s. His departure came after Archdiocese of Baltimore officials interviewed two more Keough students, who said Maskell sexually abused them.

Aug. 10, 1994 - City investigators excavated a pit in Holy Cross Cemetery in Brooklyn Park, seeking records buried there in 1990 on Maskell’s orders while he was pastor at Holy Cross Church.

Aug. 24, 1994 – Two former students of Archbishop Keough filed a $40 million dollar lawsuit against Maskell and a retired gynecologist, Dr. Christian Richter, 79, accusing them of sexual abuse at the school.

In 1996, the Maryland Court of Appeals ruled that the lawsuit could not go forward. The women had argued they should be allowed to sue even though the statute of limitations expired, because they had only recently recovered memories. The court rejected the women’s argument.

Nov. 4, 1994 - A $6,000 dollar reward is offered by the Archdiocese of Baltimore and Metro Crime stoppers for information leading to the conviction of the killer of Sister Cesnik.

December 1994 - Maskell, who left his Elkridge parish in July 1994, officially resigned from the St. Augustine's post.

1994 - According to police, Maskell is not considered a prime suspect in the Cesnik case at this time, but he is interviewed "at length."

Jan. 3, 1970 – Sister Cesnik’s partly clad body was found by two hunters, a father and son, in a remote area in Lansdowne in Baltimore County. The body, partially hidden by an embankment and snow covered, was discovered about 100 yards from the 2100 block of Monumental Avenue. Police said it was probable that Sister Cesnik had been carried to the area or forced to walk there. (A car could not have been driven from Monumental Avenue to where the body was found.). An autopsy revealed a skull fracture caused by a blow to Sister Cesnik’s left temple by a blunt instrument. Baltimore County Police take over the homicide investigation, which remains open to this day.

1970 - 1977 - According to a timeline provided by Baltimore County Police, the Sister Cesnik case was extremely active during this period: "Detectives conduct numerous interviews and polygraphs. Physical evidence from the scene is collected and preserved; relatively little physical evidence is found at the crime scene. Because of the poor condition of the body, detectives are unable to determine if Sister Cesnik had been sexually assaulted."

After 1977 – The Sister Cesnik case becomes dormant. According to a timeline provided by Baltimore County Police: "During this period, detectives receive little new information. They receive no calls from witnesses nor from victims alleging sexual abuse from associates of Sister Cesnik’s in the Catholic Church."1992 - The first allegations of sexual abuse are made against Rev. A. Joseph Maskell, a Catholic priest, by two former female students of Baltimore’s Archbishop Keough High School. Maskell denies the allegations, which are investigated by city police.

Maskell grew up in northeast Baltimore and graduated from Calvert Hall College. He trained for the priesthood at St. Mary’s Seminary in Roland Park. He was ordained in 1965. He was a school chaplain and counselor at Archbishop Keough from 1967 to 1975. He served at several local parishes: Sacred Heart of Mary from 1965 to 1966; St. Clement (Lansdowne) from 1966 to 1968 and from 1970 to 1975; Our Lady of Victory from 1968 to 1970; Annunciation from 1980 to 1982; Holy Cross from 1982 to 1992; and St. Augustine’s (Elkridge) from 1993 to 1994. He earned a master’s degree in school psychology from Towson State in 1972. He also earned a certificate of advanced study in counseling from Johns Hopkins University. He served as a chaplain for the Maryland State Police and Baltimore County Police and Maryland National Guard and later the Air National Guard as a Lieutenant colonel.

1992 - Maskell, pastor of Holy Cross Church in South Baltimore, was removed from his position by the Archdiocese of Baltimore following accusations of sexual misconduct.

October 1992 – April 1993 Maskell stayed at the psychiatric hospital, “Institute of Living,” located in Hartford, Conn. He “returned to Baltimore after an evaluation found no psychological or sexual abnormalities,” according to a 1994 Sun article.

August 1993 - Maskell was named pastor of St. Augustine’s in Elkridge after an investigation by the archdiocese did not corroborate sexual abuse allegations, according to the church.

Spring 1994 - A former Archbishop Keough student tells Baltimore County police that Maskell sexually abused her and took her to see Sister Cesnik’s body weeks before it was discovered on Jan. 3, 1970. The student also told police that another man she met in the priest’s office told her he had beaten Sister Cesnik to death because the nun knew of the alleged sexual molestation. Police note inconsistencies in the student’s account.

The student said the priest and the other man – whom she did not identify – warned her that she would suffer the same fate if she told her story to anyone else. Police were unable to verify or disprove the woman’s allegations. But in interviews with police and The Sun, she provided details about the body that were known only to investigators at the time.

July 31, 1994 - Maskell left his parish at St. Augistine’s in Howard County to seek therapy in the face of mounting allegations of sexual abuse. A least a dozen women alleged that Maskell abused them while they were students and he was a counselor at Archbishop Keough during the late 1960s and 1970s. His departure came after Archdiocese of Baltimore officials interviewed two more Keough students, who said Maskell sexually abused them.

Aug. 10, 1994 - City investigators excavated a pit in Holy Cross Cemetery in Brooklyn Park, seeking records buried there in 1990 on Maskell’s orders while he was pastor at Holy Cross Church.

Aug. 24, 1994 – Two former students of Archbishop Keough filed a $40 million dollar lawsuit against Maskell and a retired gynecologist, Dr. Christian Richter, 79, accusing them of sexual abuse at the school.

In 1996, the Maryland Court of Appeals ruled that the lawsuit could not go forward. The women had argued they should be allowed to sue even though the statute of limitations expired, because they had only recently recovered memories. The court rejected the women’s argument.

Nov. 4, 1994 - A $6,000 dollar reward is offered by the Archdiocese of Baltimore and Metro Crime stoppers for information leading to the conviction of the killer of Sister Cesnik.

December 1994 - Maskell, who left his Elkridge parish in July 1994, officially resigned from the St. Augustine's post.

1994 - According to police, Maskell is not considered a prime suspect in the Cesnik case at this time, but he is interviewed "at length."

1994 – 2000s - DNA profiles of about a half-dozen suspects are developed and compared to the known crime scene sample, with negative results, according to Baltimore County Police.

February 1995 - Cardinal William H. Keeler’s permanent revocation of Maskell’s priestly duties is made public.

May 2016 – The Archdiocese of Baltimore posted a list of dozens of priests and religious brothers accused of sexual abuse. The list, posted on the archdiocese website, includes the names of 71 clergymen about whom church officials have received what they call "credible" accusations during the priest's lifetime. All of the names, including Maskell’s, had previously been disclosed by the church.

November 2016 - The Archdiocese of Baltimore acknowledges it paid a series of settlements to people who alleged they were sexually abused by Maskell. Since 2011, the archdiocese has paid a total of $472,000 in settlements to 16 people who accused Maskell of sexual abuse. But he was never criminally charged.

2016 - Baltimore County Police reassigned the Sister Cesnik case due to the retirement of detectives. According to a timeline provided by police: “Activity on the case intensifies as victims of sexual abuse discuss information about Sister Cesnik’s circle, including Maskell. Numerous interviews are conducted. One living suspect is reinterviewed.”

Feb 28, 2017 – Baltimore County Police exhumed Maskell’s body to compare his DNA with crime scene evidence from the Sister Cesnik case. Maskell's body was exhumed Feb. 28 at Holy Family Cemetery in Randallstown and returned to the grave the same day, county police spokeswoman Elise Armacost said.

May 2017 – Baltimore County Police received an allegation from a woman who said she was abused by a now-deceased county officer associated with Maskell and the Cesnik case, Armacost said. But the woman wanted to remain anonymous, Armacost said, and declined to be interviewed by police.

May 4, 2017 - County police said they were also exploring possible connections between Cesnik's death and those of three others whose bodies were found in other jurisdictions: 20-year-old Joyce Helen Malecki, who disappeared days after the nun did and whose body was found at Fort Meade; 16-year-old Pamela Lynn Conyers, whose body was found in Anne Arundel County in 1970; and 16-year-old Grace Elizabeth "Gay" Montanye, whose body was found in 1971 in South Baltimore.

May 17, 2017 – Baltimore County Police announce that Maskell’s DNA does not match evidence from Sister Cesnik’s crime scene. Police said they received results from a forensics lab in Virginia that excluded Maskell as a contributor to the DNA from the scene. Armacost said the results don't necessarily clear Maskell as a suspect. They mean current forensic technology doesn't provide a physical link between him and the crime scene, she said.

May 19, 2017 – Netflix is scheduled to release “The Keepers,” a documentary series on the unsolved killing of Sister Cesnik. (Trailer video)

Compiled by Sun researcher Paul McCardell

February 1995 - Cardinal William H. Keeler’s permanent revocation of Maskell’s priestly duties is made public.

April 1995 - Baltimore County Police return the unsolved case of the slaying of Sister Cesnik to the “cold case” file.

May 7, 2001 – A. Joseph Maskell died at St. Joseph’s Hospital. He was 62 years old.May 2016 – The Archdiocese of Baltimore posted a list of dozens of priests and religious brothers accused of sexual abuse. The list, posted on the archdiocese website, includes the names of 71 clergymen about whom church officials have received what they call "credible" accusations during the priest's lifetime. All of the names, including Maskell’s, had previously been disclosed by the church.

November 2016 - The Archdiocese of Baltimore acknowledges it paid a series of settlements to people who alleged they were sexually abused by Maskell. Since 2011, the archdiocese has paid a total of $472,000 in settlements to 16 people who accused Maskell of sexual abuse. But he was never criminally charged.

2016 - Baltimore County Police reassigned the Sister Cesnik case due to the retirement of detectives. According to a timeline provided by police: “Activity on the case intensifies as victims of sexual abuse discuss information about Sister Cesnik’s circle, including Maskell. Numerous interviews are conducted. One living suspect is reinterviewed.”

Feb 28, 2017 – Baltimore County Police exhumed Maskell’s body to compare his DNA with crime scene evidence from the Sister Cesnik case. Maskell's body was exhumed Feb. 28 at Holy Family Cemetery in Randallstown and returned to the grave the same day, county police spokeswoman Elise Armacost said.

May 2017 – Baltimore County Police received an allegation from a woman who said she was abused by a now-deceased county officer associated with Maskell and the Cesnik case, Armacost said. But the woman wanted to remain anonymous, Armacost said, and declined to be interviewed by police.

May 4, 2017 - County police said they were also exploring possible connections between Cesnik's death and those of three others whose bodies were found in other jurisdictions: 20-year-old Joyce Helen Malecki, who disappeared days after the nun did and whose body was found at Fort Meade; 16-year-old Pamela Lynn Conyers, whose body was found in Anne Arundel County in 1970; and 16-year-old Grace Elizabeth "Gay" Montanye, whose body was found in 1971 in South Baltimore.

May 17, 2017 – Baltimore County Police announce that Maskell’s DNA does not match evidence from Sister Cesnik’s crime scene. Police said they received results from a forensics lab in Virginia that excluded Maskell as a contributor to the DNA from the scene. Armacost said the results don't necessarily clear Maskell as a suspect. They mean current forensic technology doesn't provide a physical link between him and the crime scene, she said.

May 19, 2017 – Netflix is scheduled to release “The Keepers,” a documentary series on the unsolved killing of Sister Cesnik. (Trailer video)

Compiled by Sun researcher Paul McCardell

MARCH 1 2018 UPDATE

NOTES FROM THE KEEPERS

WHO KILLED SISTER CATHY? (1942-1969)

Went missing: Nov 7, 1969

Body found: Jan 3, 1970

Where: near a garbage dump in the Baltimore suburb of Lansdowne

Cause: intracerebral hemorrhage caused by skull fracture

Tom Nugent, journalist 1994

Gemma Hoskins, former student of Cathy's

Abbie Schaub Fitzgerald, former student of Cathy's

Deb Silcox, former student of Cathy's

Juliana Farrell, former student of Cathy's

Bob Erlandson, journalist

Mary Spence, Keough student

Gerry Koop, former priest

Pete McKeon, former priest

Capt John Barnold, Baltimore City Police chief of homocide investagation in 1970

James Scannell, former Capt of Baltimore County police, first officer on scene when Cathy's body found

Bud Roemer, M (Murder/Homocide) Squad Capt for Baltimore County police, in charge of all criminal investagations

Don Malecki, Joyce's brother

FACEBOOK PAGE

Justice for Catherine Cesnik and Joyce Malecki

https://www.facebook.com/JusticeForCathyCesnik/

Season 1 Episode 1

"We're told the story is not the nun's killing.

The story is the coverup of the nun's story."

Abbie Schaub

"Sister Catherine and Sister Russell, they were roommates. They taught together at Keough and they were the two nuns who left the order, became public school teachers."

Bob Erlandson

Q1. DID CATHY AND RUSSELL LEAVE THE ORDER AND NO LONGER WERE NUNS?

"As far as we know, she (Cathy) left the apartment parking lot (Carrage House Apartments, 131-139 N Bend Rd, Baltimore, MD 21229) somewhere around 7:00 pm. Sister Russell, her roommate, said this was a routine that they did. She was going to go shopping to pick up some bakery buns, she was going to buy an engagement gift for her sister. She went from her apartment to the Edmondson Village Shopping Center."

Abbie Schaub

"Sister Cathy went to the local bank, cashed her paycheck, bought some dinner rolls. Now accounts vary here - several witnesses have told the newspaper and the police, there's no doubt that nun returns to her parking space but no one has proved that she ever came back to her apartment. Instead she vanished."

Ted Nugent

"We have a witness, an airline stewardess had gone grocery shopping and was going up and down from her car, carrying bags of groceries in and out. On the third trip, about 8:30 pm, she remembers seeing Cathy sitting in her car in the parking lot, as if she were waiting for something."

Abbie Schaub

"... early November... Friday night... we heard this yealling and I would say it came from that direction, that's where Sister Cathy and Sister Russell lived (a block or so away). It was a man's voice, loud, booming, garbled with emotion, anger. We really thought it was some kind of violence that was going on up there."

Mary Spence

"Around midnight, she (Sister Russell) became concerned enough that she called Gerry Koob... Cathy and Gerry apparently developed a friendship. That troubles us a bit, looking back, why didn't sister Russell call the police?"

Abbe Schaub

Q1. WHY WAS RUSSELL'S FIRST CALL TO KOOB AND NOT TO THE POLICE?

"... I knew then Brother Peter, Pete McKeon and I had decided there's a movie playing in Baltimore tonight that we both want to see. It was Easy Rider. I would venture it must have been about 10:30 pm or so by the time I got back (Beltsville is 40-45 min from Baltimore and Cathy's apt). And we were sitting and talking about it and the phone rings and it's Sister Russell Phillips: "Have you seen Cathy?" She tells us, "Cathy went out around 8 or 8:30 pm. She was going to get an engagment present for her sister and she's not home yet." So we got in the car and drove up to Catonsville (They were in Beltsvile which is 40-45 min from Cathy's apt which is about 7 mi from Catonsville) immediately."

Gerry Koob

Q1. KOOB SAYS RUSSELL SAID CATHY LEFT 8:00 PM OR 8:30 PM BUT PREVIOUS STATEMENTS SAY 7:00 PM. WHY?

"We spent maybe 45 min to 1 hr listening to Russell and since it was now 3 hrs after what she expected, it's time for us to call the police. So a single policeman responded to our call. He came to this apartment. We were describing her as a missing person. He wrote everything down. He left. The three of us gathered around a little table and I said mass. We put a little bread and wine and I did the mass of consecration. And we saved some of the communion bread for Cathy. We were still hoping

against hope that she would show up. After another hour or two (4:00 am?), Peter and I left and went down those steps to take a walk. We were coming up this way and when we get about here (across the street from apartment), we spot the car. This door was unlocked. We went in and the famous twig was sticking, hanging down from that."

Gerry Koob

"There are leaves, twigs, muddy tires. This car had been into a swampy area. Kinda questionable. The car had been into swampy, muddy ground. And why is that car found with its rear end sticking out in the street, right adjacent to the Carrage House apartments where the num lived? Whoever put that car there, wanted it to be found."

Ted Nugent

"Sister Cathy and Joyce (Malecki) went missing in the same area in west Baltimore, in the same week so we've been working with the Malecki family to try and get information about Joyce and make connection between the two murders and the people that we think were responsible."

Gemma Hoskins

"City police search for missing nun. Twenty-six officers combing area with canine corp dogs. It's a hugh public event in 1969. We've got a terrible nun disappear - it's all over the front page. And 5 days later, oh my God, what's happened to Malecki? Are they connected? And the FBI commissioner, the head guy in Baltimore anyway, tells the press, "Rest assured. Your Federal FBI is hard at work. We will find out if there's a connection between Malecki and Sister Cathy. You start asking, who ran that investigation? And that's Capt John Barnold. He's the chief of homicide Baltimore

City cops."

Ted Nugent

"From day one, Barnold is essentially telling everybody, well we don't think it's a kidnapping, we don't see problem, we're ok, we're going to be fine. What's going on here? Where is she? We can't find her. We don't know. Nobody knows."

Ted Nugent

"From Nov 7 till mid January, I had no idea what happened to Cathy."

Gerry Koob

Q. Mid January? Her body was found Jan 3.

"I can remember, I was leaning against a wall when somebody was telling me they found the body. And I remember sliding my back down the wall to sit on the floor. And mostly the feeling was relief. You know, now the waiting to find out what happened is over."

Gerry Koob

Q. Relief?

"... she hadn't deteriorated. No maggots or anything like that."

James Scannell

NOTE: The autopsy report says there were maggots.

Ted Nugent reading news article, "... Roaming the autopsu, (Bud) Roemer soon found himself contemplating a likely scenero. A stranger probably abducted Cesnik from the Edmondson Village Shopping Center on Edmondson Ave near her apartment. In all likelyhood, the unknown assailant then killed the nun and dumped her body about 5 miles away. But his hypothsis was contradicted by one troubling fact. The nun's car, a green 1964 Ford Maverick had been parked in an odd angle illegally near her Carriage House apartment complex only a few hours after she drove off to the shopping center. How had the dead woman's Ford gotten back to the apartment complex? In that situation, the killer wants to get the h___ away from there. Last thing he wants is to return to area where he might be spotted driving the victim's car."

Ted Nugent

"The cops always told us there was no forenisic evidence in that car. But the fact of where the car was parked combined with the fact of where her body was found some months later, is a detail that's always been stuck in my throat because where her body was found is not an area where you would casually drive by it and say oh here's a good place to dump a body. But this was a very out of the way area, which led me to believe it was somebody who knew that area very well."

Bob Erlandson

"I've been pursuing this for the last 15 years. I've been calling FBI and time in and time out, and I get the same answer. I visited them, I went and knocked on their door, what have you done in the last 15-20 years? And the only thing they tell me is, it's an open case and we cannot discuss it. It almost leads me personally to believe, it's a coverup because I can't get any information."

Don Malecki

"A retired detective that I interviewed frequently, who worked on it, often says to me, Nugent, the real problem here is the coverup itself. The coverup itself is the cancer inside Baltimore."

Ted Nugent

--- END---

Jean Hargadon - Jane Doe, former student of Cathy's

Ed Hargadon - Jean's brother

Mike Hargadon - Jean's brother

Don Hargadon - Jean's brother

Bob Hargadon - Jean's brother

Lil Hughes Knipp - Keough class '71

Teresa Lancaster - Jane Roe, Keough class '72

Kathy Hobeck - Keough class '70

Donna Vondenbosch - Keough class '74

Edward Neil Magnus (1937-1988) - abusive priest at Keough

Anthony Joseph Maskell (1939-2001) - abusive priest, chaplain & counselor at Keough

Brian Schwaab, former detective Baltimore City Police

Lyn Smith, former nun

Cecelia Wambach, former nun

Brother Bob, abusive priest

Tommy Maskell, Baltimore city policeman & brother of Joseph

Season 1 Episode 2

"I believe that Cathy Cesnik was murdered by someone she knew. I believe that it wasn't a stranger who killed Cathy Cesnik. It may have been a stranger to her who moved her body or a stranger to her who cleaned up after, but, I don't believe it was a stranger who killed Cathy Cesnik. Cathy Cesnik was killed because she was going to talk about what went on at that school and I believe that there were more than one person who was really afraid that she was going to out them. And they used her death to keep me quiet."

Jean Hargadon

"We were soulmates. I was her best friend and she was mine. We first got aquainted in the summer of '66. We were corresponding in letters by July of that summer. And I would say we discovered a real geniune love of each other at that time. There were very few people who knew what our relationship was. There was no going out somewhere to dinner or anything like that, we couldn't do it. She was facing a crossroads in her life because she was coming up on the expiration of her temporary vows. The nuns took vows for x number of years. But then they reach the point of shifting of taking temporary vows to final vows. And she was facing that. I was still a year away from being ordained. We're sitting next to each other outside at Keough. It was a warm day and we're sitting side by side. And I said to her, I feel like I'm about to jump off a cliff but I'm going to do it anyway. You're facing a decision of going to take final vows. A year from now I will face the decision to become a priest and I want to say no to both and ask you to be my wife. And she turned me down. She said, no you're meant to be a priest, I'm meant to be a nun, so we'll go on."

Gerry Koob

"Cathy's delimea, we are not in touch of where these girls are coming from. We don't know what it's like to be living in the world. We're protected behind this convent thing which limits our understanding of what a teenage girl is going through. She had gotten permission from her local superiors to try living outside

the convent in an apartment in Catonsville with Sister Russell. This is what she looked like when she left Keough to go teach in a public school while remaining a nun."

Gerry Koob

"Cathy Cesnik and Russell Phillips were trying this experiment. I understood that Mother Mauruce (Kelly) gave permission to experiement with teaching in public high school and being nuns out in the regular world. I was surrised that they were the ones engaging in this. They were complient nuns, following the rules all the time."

Cecelia Wambach

"Two days before Cathy disappeared, a friend and I went to her apartment casually for a visit and we talked shortly because my friend didn't know what was going on. Sister Cathy asked me how things were and I knew what she meant. I was hesitant to answer. And she says, It will be taken care of, don't worry.

Kathy Hobeck

"We know there was a third woman who was in Sister Cathy's apartment the night before Cathy disappeared. She and her boyfriend arrived to visit the two sisters, Cathy and Russell, and she was sharing with Cathy about the abuse. And Joseph Maskell and Neil Magnus came into the apratment without knocking. I asked specifically what expressions were on their faces and she said Maskell was furious, Magnus looked dumb."

Gemma Hoskins

"So Cathy sent her out and her boyfriend out of the apartment. The next day when she went to school, he called her into his office and said, If you say anything I'll kill both of you and your families. She never said anything."

Deb Silcox

"Later that day is when Cathy disappeared. This woman who has chosen to remain anonymous has lived with fear all her life."

Gemma Hoskins

"Cathy and I were supposed to get together the day after she was actually killed."

Gerry Koob

Q. HOW DOES KOOB KNOW WHAT DAY CATHY WAS KILLED?

"She said there was something very serious she wanted to talk to me about. I though she might want to reopen the question whether or not we want to leave and get married. But I look back now and if at that time she was aware of priests sexually abusing the girls at Archbishop Keough, then maybe that's what she wanted to talk about. Would have been a h___ of a conversation. But it never happened."

Gerry Koob

"I was called to the room and it was after school. And he (Maskell) was frantic. I know you're really close with Sister Cathy and I wanted to let you know she's missing but I know where she is. And I was, What do you mean? You know where she is? He says, Yeah I know where she is. Do you want me to take you to her? And I was like, Yes! We leave his room. I remember walking through the corridor of the school and we go out and get in a car. There are two unbelievable emotions going on at the same time. One was total shock, What do you mean she's missing? It hit me like in the stomach. And the other was, he knew where she was, relief. I just knew I needed to see her. We pull up into this barren area. There was grass and dirt and I'm thinking, What is she doing here? And I'm following him and he moved over. And there was a ? on the ground and I knew it was her. Before I knew it, I was kneeling down next to her and there were maggots in her face and I was wiping her facing saying, Please help me, please help me, please help me, please help me. And I'm looking at my hands and he came down real close and he said, Do you see what happens when you say bad things about people?

Jean Hargadon

--- END ---

MARCH 7, 2018 UPDATE

IN THE COURT OF APPEALS

September Term, 1995

No. 102

JANE DOE, et al.

Appellants

v.

A. JOSEPH MASKELL, et al.

Appellees

--- END ---

JUNE 6, 2017 NEWS ARTICLE

http://www.baltimoresun.com/news/maryland/bs-md-maskell-ireland-20170605-story.html

'Keepers' priest Maskell spent time in Ireland, now under scrutiny

Public health officials in Ireland say they are reviewing the work history of A. Joseph Maskell, a Catholic priest profiled in the Netflix series “The Keepers.”

Alison KnezevichAlison KnezevichContact ReporterThe Baltimore Sun

Public health officials in Ireland say they are reviewing the work history of the Catholic priest profiled in the Netflix series "The Keepers," who was employed as a psychologist in that country after leaving Baltimore amid sexual abuse allegations.

The priest, A. Joseph Maskell, worked in Wexford for about seven months in 1995 as a temporary clinical psychologist for an Irish public health board, according to the national health agency there. He later worked in private practice in Ireland between 1995 and 1998, church officials in Ireland say.

He died in 2001 at St. Joseph Medical Center in Towson.

The Health Service Executive, the agency that runs public health services in Ireland, said in a statement that it has begun a process to "review services delivered and regarding any concerns" about Maskell's employment with the public South Eastern Health Board.

The review comes in the wake of publicity from the seven-part Netflix documentary "The Keepers." The series examines sexual abuse at Archbishop Keough High School and the unsolved 1969 homicide of 26-year-old Sister Catherine Ann Cesnik, who taught there.

Police: Exhumed priest's DNA does not match evidence from crime scene killing of Sister Cathy

Maskell, who served as chaplain and counselor at Keough, left the United States as allegations against him mounted in the 1990s. The Archdiocese has paid $472,000 in settlements to 16 people who alleged abuse by Maskell. He was never criminally charged, and denied abuse accusations before his death.

In a statement, the Health Service agency said Maskell worked for the South Eastern Health Board between April and November 1995. The agency said that as part of the hiring process, Irish police checked whether he had any prior convictions. He did not.

Asked whether Maskell assessed any children or teens while working for the health board, a spokesman for the agency said it could not provide any additional information pending the outcome of the review.

Baltimore church officials have said they barred Maskell from public ministry in 1994 and that he went to Ireland without their knowledge. They said they learned in 1996 he was living in Wexford.

Maskell was born in Baltimore, but his family was from Ireland, said Baltimore archdiocese spokesman Sean Caine.

Teresa Lancaster, who was featured in "The Keepers" as an abuse survivor, said Maskell spoke about Ireland when he was working at Archbishop Keough.

"When he took me to the rectory, he would put on Irish music and tell me how wonderful it was," Lancaster said.

Baltimore attorney Joanne Suder, who has represented people with abuse claims against Maskell in recent years, said she has received numerous phone calls about him since "The Keepers" was released. She said three people with knowledge of his time in Ireland have told her that Maskell presented himself as both a psychologist and a priest and that "he had access to young girls."

"That's frightening," she said.

Maskell also celebrated Mass in Ireland even though he had been prohibited from public ministry in the United States, Irish church authorities told The Baltimore Sun.

Pictures: The Catherine Cesnik case

Catherine Cesnik, a 26-year-old nun, disappeared after leaving her Southwest Baltimore apartment to go shopping in November 1969. Two months later, her body was found in a frozen field in Baltimore County. Catherine Cesnik case: Archived Sun coverage

> Licensing inquiries: Email tim.thomas@baltsun.com

The Rev. John Carroll, a spokesman for the Diocese of Ferns, said in a statement that Maskell first had contact with diocesan officials there in 1995 when they discovered he celebrated Mass as a substitute for a priest who was ill.

After being contacted by the Ferns diocese, Maskell replied in a letter in April 1995.

"I wish only to offer Mass privately and carry out my spiritual activities in a like manner," Maskell wrote, according to Carroll.

The diocese sent a follow-up letter to Maskell asking for confirmation of his status as a priest, but received no response, Carroll said.

In June 1996, the Diocese of Ferns contacted the Archdiocese of Baltimore to clarify Maskell's status as a priest.

"Baltimore explained to Ferns that serious allegations had surfaced regarding Fr. Maskell prior to his departure from that diocese in 1994," Carroll said in the statement. "Baltimore stated that it had been unaware of Fr. Maskell's current whereabouts. Baltimore immediately contacted Fr. Maskell and restated its prohibition on his ministering in public."

The Ferns diocese also contacted the health board in Ireland and "aired its anxieties" about Maskell's work as a psychologist, Carroll said.

The health board said that by the time it received correspondence from the diocese, Maskell was no longer working for the health board. But the file shows Maskell was working as a psychologist in private practice, according to Carroll.

Maskell worked privately in Wexford and Castlebridge from 1995 to 1998, Carroll said, and on occasion presented himself as a priest.

The Ferns diocese's file on Maskell, which has not been released publicly, covers a period from April 19, 1995, to Sept. 22, 1998, Carroll said. It is not clear from the file when Maskell arrived in Wexford and when he departed, he said.

Carroll said the Ferns diocese has not received any allegations of abuse by Maskell.

In the United States, there have been calls for the Archdiocese of Baltimore to release its files on Maskell, but church officials say they will not do so. An online petition posted on the website change.org has garnered more than 6,400 signatures.